Memory in the Garden

Wet Prairie

I've chosen to make a variation on a wet prairie, an ecological model appropriate to my site, and one that probably can sustain the visual and aesthetic interest I want. I'm not at all certain wet prairies have existed in New Jersey

Mine will be maintained by cutting and periodic burning, with no soil improvement other than what the plants, animals and insects do themselves. I'm using many natives, but also exotics if they grow well in my conditions, and taking a wait and see approach, letting the plants find their favored positions, and intervening only to keep harmony. It's to be a garden "in tune with nature." In regard to sense of place, that's my garden's story from a practical and ecological perspective.

Sense of Place

But sense of place is broader than environmental or ecological setting. The garden also exists in cultural and historic contexts, and I do want to consider those aspects of place, in a subtle way that does not shout for attention - and certainly not in a pedantic or dry academic fashion.

The word “historic” is freighted with negative connotations for many and can be off-putting. In a lecture on history in the garden, given as part of the Vista lecture series in London (see this link), noted UK landscape architect Kim Wilkie suggests that substituting the word "memory" for "history" makes it much easier to think about these issues in more personal terms: "I think what we need to do is understand what a landscape is about, the ghosts that are there, the feelings that are there, the memories that are there ... It is looking at the daubs and the tears and the hieroglyphs and allowing that, hopefully, just to give you the charge to continue the story..." Wilkie's analogy to an old manuscript is appropriate. Like a palimpsest, it carries virtually invisible messages from the past.

Blue Jingle

The rock around here is called "blue jingle." It has a bluish color and makes a metallic clink when you strike one stone against another. The scientific name is argillite, a sedimentary stone formed at the bottom of ancient lakes in the Triassic period, about 200 million years ago. (You can see it in the photo on the right, exposed in the bed of Lockatong Creek.) This stone does not fracture easily, and it is extensive in the geology of this area, making for water supply aquifers that yield comparatively little water. More important for gardeners, it slows percolation of water into the soil, keeping rainwater and snow melt near the surface, and creating a huge amount of runoff during storms. As a consequence of the qualities and distribution of blue jingle, we garden in shallow, wet soil on Federal Twist Road

So the conditions under which I garden and my plants must grow are ordained by the geological history and the climate of this place. I accept this and work with it.

History and Culture

White Europeans have lived in these hills for over 350 years; they have left many artifacts. They cleared their fields of stones, making long, intersecting stone rows that separated the fields. These rows extend throughout the surrounding woods today. My property is bounded by long, capacious rows of argillite, which I'm using to build dried laid stone walls that are, in a real sense, monuments to the local geology, and to the European settlers who first cleared the land of rocks to make it farmable.

The aboriginal people of this area, the Lenni Lenape, lived here for many thousands of years, far longer than we of European descent, yet left hardly a trace. It's too easy to forget their long stewardship of the land, and their gradual loss of their place and way of life. The absence of signs of their existence speaks loudly of how they lived and passed from here. Their memory should be marked by some silent sign.

So too the newcomers, the builders of our house, the Howeths, who asked a notable local architect, William Hunt, to design it in 1964. I have 35mm slides of William Hunt surveying the site just a few days before JFK was assassinated, and many others showing open fields dotted with small junipers, and the original landscaping. Little is left of that but the images, several trees planted around the house, and a carpet of myrtle that remains from that time.

My Garden’s Story

This is the rough material for my garden's story. As I learn to read the land, watch the movement of water over its surface, observe the changes in vegetation with increased sunlight, imagine how the land has changed over historic as well as geologic time, and learn more about the human past, I also have begun to see a design, an abstract structure emerging - first the circular shape of the clearing that is the main feature of the garden, then the lines, circles and rounded forms that signaled life in the forest - curved trails, straight stone walls, meandering paths, and the circular blot of a dead fire.

Garden Design

When I first started this garden I was not aware of its past, only of the shapes that work naturally here. Taking the great circle of the clearing in the woods as a pattern, I repeated it at different scales to begin to create structure.

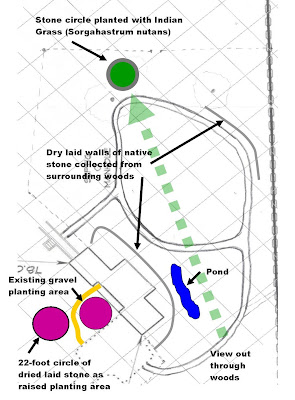

The simple plan shows the garden design emerging from repetition of lines, curves, and circles. The two circles shown in violet at the front of the house, one of gravel, the other of dry laid stone, screen the entrance and provide raised areas with relatively dry planting conditions.

These are reflected in the long curved path running from the front of the house around to the main garden area in the back.

The curved path is reflected, in turn, in the curve of another stone wall to the left, running around the end of the house and across the back, all of this at the base of a mound on which the house rests, to keep it above the surrounding wetness. As you walk the path to the back, this curved wall opens the view to reveal the main garden space, and creates a kind of momentum pulling you along from front to back.

Across the garden from the house, a second curved stone wall (shown below), much lower than the one at the base of the house, visually encloses the garden space and helps define it as separate from the forest behind. The large dotted arrow on the plan indicates the most distant view out through the forest wall surrounding the garden but, in fact, all views are into forest.

At the back of the garden, opposite the pond and balancing it visually, could be a final feature that exists only in concept and is still subject to change. It could be a circle about 25 feet in diameter, with a flat stone perimeter perhaps three to four feet wide. The center of the circle would be planted with native Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans). The stone would be argillite. This would be a visually prominent feature, and would acknowledge the people who originally inhabited this ridge above the Delaware

James Golden