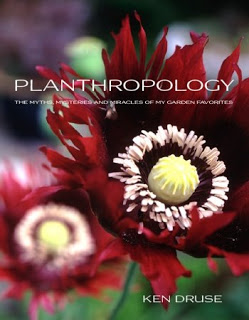

Planthropology: The Myths, Mysteries, and Miracles of my Garden Favorites by Ken Druse

We’ve grown to expect beautiful books from Ken Druse, notable for his excellent photography, and an easygoing style that makes for a good read. I enjoyed this book and, as with Ken's other works, I’ll go back to it to recollect a fact, get a jolt of visual stimulation, or just to pass the time in pleasurable reading about gardening and plants. The publication is just in time for the holiday season. The eye-catching dust jacket, with big red poppies yearning for your attention, makes it just look perfect as a Christmas or Hanukkah gift.

We’ve grown to expect beautiful books from Ken Druse, notable for his excellent photography, and an easygoing style that makes for a good read. I enjoyed this book and, as with Ken's other works, I’ll go back to it to recollect a fact, get a jolt of visual stimulation, or just to pass the time in pleasurable reading about gardening and plants. The publication is just in time for the holiday season. The eye-catching dust jacket, with big red poppies yearning for your attention, makes it just look perfect as a Christmas or Hanukkah gift.Planthropology is a ramble through Ken Druse’s head – a very entertaining ramble – profusely illustrated with his beautiful photographs, and rather lavishly produced. Though the book has a clear structure, it’s really a miscellany (in a good sense) full of personal reminiscences and anecdotes, intriguing plant lore, history, and an occasional dose of science.

Ken tells the stories of plants. He writes about the heroic adventures of early plant explorers, about evolution and surviving “living fossils” like the ginkgo and dawn redwood, the uses of plants through history (as food, medicine, poison), the universal patterns governing the growth and structure of plants, seashells, and other natural phenomena. But trying to list its subject matter is hopeless; it’s far too wide-ranging for easy summary.

This book will be an immediate draw for the plant lovers among us. Some readers will enjoy just turning the pages, looking at the pictures, reading the captions and maybe a bit of the text here and there. Others will read the book from cover to cover, as I did, then return, dipping into the flow of prose almost at random. You can easily drop in at any point.

Although the book is structured into major sections organized around broad themes, Ken takes every opportunity to segue into diversions on particular plants, personal reminiscences, his experience growing his favorite plants, or any number of other interesting side stories. This loose structure is what makes the book so easily accessible.

Perhaps one of the greatest virtues of this book may be its clearly stated goal to capture the interest of people, especially children, who are unaware of plants. The last chapter in the book begins with a discussion of what Dr. Peter H. Raven, director of the Missouri Botanical Gardens, calls “plant blindness” – the inability to most Americans to even see plants, much less know their names or anything about them. Planthropology is full of the kind of information about plants that could delight children, that parents could use to reduce “plant blindness” in future generations of potential gardeners and, in doing that, contribute to an awareness of the natural world, and a concern for preserving it.

(photo: Clarkson Potter)

James Golden