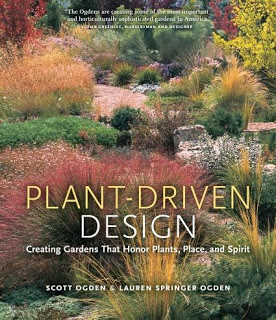

Plant-Driven Design: Creating Gardens that Honor Plants, Place and Spirit

Plant-Driven Design by Scott and Lauren Springer Ogden is a beautifully produced book about using plants in creative combinations, and in communities, to create gardens sublimely suited to their environments. The attention-grabbing name, the high production value with loads of photographs mostly by Lauren Springer Ogden, and the sophisticated “how to” approach, profuse with anecdotes and examples from the Ogden's own experience, may gain this book a significant readership.

Plant-Driven Design by Scott and Lauren Springer Ogden is a beautifully produced book about using plants in creative combinations, and in communities, to create gardens sublimely suited to their environments. The attention-grabbing name, the high production value with loads of photographs mostly by Lauren Springer Ogden, and the sophisticated “how to” approach, profuse with anecdotes and examples from the Ogden's own experience, may gain this book a significant readership.The Ogdens wrote Plant-Driven Design to get your attention. The book clothes an old idea—plant the right plant in the right place—in western (that's the North American west) drag, and serves it up as a new way to make gardens. The Ogdens are opposed to all the commercial and cultural influences that keep people from actually coming into contact with their gardens and experiencing plants first hand—the design/build landscapers who install the hardscape and garden (mostly high-profit hardscape) as a package deal, the legitimate landscape architects who know garden planning as a profession but know little of plants, garden designers who design beautiful gardens but leave their clients ignorant owners of gardens they don't love and can't properly care for. They are, in fact, stating their opposition to all the forces that make people indifferent to plants and keep them from learning about plants, or even wanting to.

Fighting ignorance is a difficult thing when the ignorant don't know they are ignorant. Perhaps this is one reason the authors adopted such a self-consciously provocative title. They repeat “plant-driven design” like a mantra throughout the book; it has a false ring, but it's a memorable rallying cry, certainly, and it will be interesting to see if it works.

The Ogdens appear intent on creating a new American garden for the wide open, mostly treeless, big sky landscape of the American west. Plant-Driven Design is a polemic—one intended to demonstrate a superior approach to gardening far more suited to the American landscape than, say, a British-influenced approach. Its focus on plants and their creative use appropriate to specific regions and microclimates still hasn't penetrated to the general gardening population in the U.S., and perhaps the Ogden's book will help spread the word.

Oddly, the Ogdens take some unusual stands, and this seems to be a direct result of their “plant-driven design” message which, in brief, suggests that if you love and understand your plants’ needs and how they grow under natural conditions, your garden’s design will emerge from closely observing plants and matching them to their environment. They recommend against designing a garden, then selecting the plants to go into it – not a bad recommendation in itself – but they go further – in fact, too far. In some passages, they appear to attack the very concept of garden design. In the opening chapter “Putting Plants First—a different approach to designing gardens” they quickly move to a discussion of “how structure-driven gardens fall short,” in which they dismiss the work of Thomas Church and Roberto Burle Marx—Church because he subjugated plants to design and Burle Marx because he turned plants into abstract art. They never talk of gardens as art, or directly discuss design. Such a narrow view of gardening does them no credit, and it relegates some great garden designers to the compost heap.

This is also a book about love of plants, and it seeks to imbue some of that feeling for plants and the generous acts of gardening in the reader. The Ogden's write powerfully about the emotional connection between gardener and garden, and about the importance of plants to making this connection. This is the heart of their book. The Ogden’s approach represents a regional offshoot of the naturalistic gardening movement begun in the 19th century by William Robinson, his followers in the UK, and the German ecological planting movement. The Ogden’s even use photos of the garden at the Weihenstephaner Institute in Bavaria, where the great grand-daddies of ecologically appropriate gardening, Karl Hansen and Friedrich Stahl, did the years of research that resulted in the classic Perennials and their Garden Habitats, though they make no mention of this seminal book. They place value not on flowers or color, but on the whole organism—structure, shape, texture, appearance through all seasons, appropriateness to environment, importance of sense of place, and plant communities that naturally evolve over time, with minimal involvement from the gardener. Where they take the book in this direction, writing about the connection between plants and their natural habitats, between garden and gardener, it is at its best.

One word of warning. Readers on the east or northwest coasts of the U.S. and in other more temperate climates will be hard pressed to find practical examples for their gardens, though underlying concepts (dare I say 'design concepts'?) are the same. There are some references to gardens in more temperate climates, but the focus is clearly on drier habitats of the west. I recommend the book primarily for residents of arid areas of North America, and gardeners in areas with Mediterranean, steppe, and alpine habitats in other parts of the world. The Ogden's dry climate approach and popularization of a broad range of plants unknown to most North American gardeners points the way to a viable future for gardening in a large part of the continent where rapidly growing population, a changing climate, and increasing scarcity of water make the Ogden's kind of gardening—they live in Colorado in the summer and Texas in the winter—a model for the water-scarce future.

I often read gardening books from cover to cover, but I had a hard time with this one; it is simply too long and in need of more rigorous editing. The writing is uneven—smooth sailing at times, at times irritating, occasionally inspiring. Nevertheless, this is an important book that may have a significant role to play in American gardening. The Ogdens should be congratulated for writing a gardening book with serious intent—something much too rare in the American garden publishing world. I'll certainly keep it on my bookshelf; it's likely to become a well worn reference over the years.

James Golden