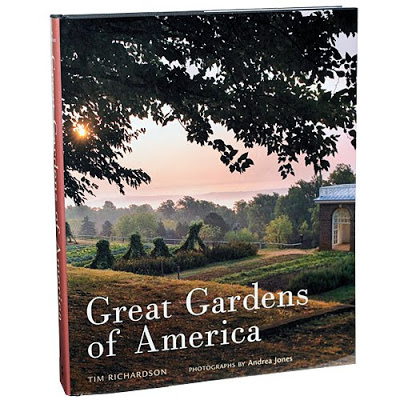

Great Gardens of America by Tim Richardson

Garden criticism hardly exists in America, and Tim Richardson is a British garden critic. What does Richardson have to say to us? If you read his new book Great Gardens of America, which I highly recommend you do, expect something new. This is one of those rare garden books of ideas. You will learn new things about gardens and the process of making and keeping gardens.

Great Gardens of America is a critical analysis of 25 gardens in North America. With many beautiful color photos by Andrea Jones and a large format, Great Gardens offers visual interest most of us seek in such books. But this is much more than a photo book of gardens. The text is more important than the pictures, which really serve to illustrate Richardson's points and pique the readers' interest. Tim has selected a disparate array of gardens, though he does find a unifying concept in all of them. He writes about how the gardens came to be, the interactions between owners and designers, cultural and historical influences of other gardens from other cultures and times, how successfully the garden designers achieved their goals, critical issues of garden maintenance and preservation. This is a book of ideas and - I mean this in the most complimentary sense - an educational book that will deepen understanding of gardens.

As Mr. Richardson points out, American gardens generally are outward looking, with an openness to the wilderness, in many cases even finding their origins in imitation of wilderness. Among wealthy classes with the resources to spend lavishly on their American gardens, and even when designing gardens highly derivative of European gardens, their Beaux Arts or Arts and Crafts gardens took on a character that was newly American, and in the end very different from their European models.

I'll quote directly from Richardson's "Introduction - What is it that makes American gardens 'American'?"

"So what is it that makes American gardens 'American'? The key difference between America's gardens and those of Europe can be traced back to this idea of a society's relationship with nature. Put simply, the American mode of gardening appears to be framed by the nation's historic embrace of the wilderness ideal. Using a necessarily broad-brush approach, it can be observed that American garden-makers have taken a much more open and embracing attitude to the concept and reality of wilderness. This is a theme that struck me time and again in American gardens, which are quite often clearly beholden to European design styles - styles which can then be seen to be have been decisively tweaked or tonally altered. In America, even in cases where the detail of the design was initially inspired by European examples, it seems that the beckoning natural landscape will often be harnessed to set the tone of the garden as a whole. Vistas in America, for example, can just as often be wide and general, as opposed to object- or building-focused, as they are in Europe. This lends many of these gardens an expansive, unbounded feel, quite at odds with the European tradition where an attempt is often made to fence out wilderness by means of enclosures. Even the English landscape park, an ostensibly 'naturalistic' approach to garden making, had as its object a highly particular version of the pastoral which often involved redevelopment of the existing topography. The view may have been expansive, but it was always clearly under control: managed. The European mindset of enclosure was given its richest artistic expression in the cellular Arts and Crafts gardens of the early twentieth century. There are several examples in this book of the ways in which the enclosure instinct was usurped or altered by American garden makers.

These differing attitudes emerged from specific historical contexts. In Britain, for example, from the medieval period, another word for wilderness or unfenced land was 'waste'; it was considered the domain of bandits and dangerous wild animals. In America such places early on became synonymous instead with the idea of plentitude and potential, at least in the mind of the populace at large, as opposed to those who actually lived out their lives on the frontier."

This is an exciting book. It is a joy on a purely visual level, and it offers much more to those who want to learn something new about some of America's great gardens, who want to better understand why they are great, how they relate to their historic precedents in other parts of the world, and why they are unique to this continent and the places in which they exist.

Great Gardens of America is a critical analysis of 25 gardens in North America. With many beautiful color photos by Andrea Jones and a large format, Great Gardens offers visual interest most of us seek in such books. But this is much more than a photo book of gardens. The text is more important than the pictures, which really serve to illustrate Richardson's points and pique the readers' interest. Tim has selected a disparate array of gardens, though he does find a unifying concept in all of them. He writes about how the gardens came to be, the interactions between owners and designers, cultural and historical influences of other gardens from other cultures and times, how successfully the garden designers achieved their goals, critical issues of garden maintenance and preservation. This is a book of ideas and - I mean this in the most complimentary sense - an educational book that will deepen understanding of gardens.

American Gardeners are no longer 'Poor Relations'

The place of American gardens within the cultural landscape of the rest of the world, especially Europe,was an issue of great concern and some embarrassment in the early days of our republic, and even well into the 20th century among such cultural icons as Edith Wharton and Henry James, who believed American culture lacked the maturity and depth of a great civilization, and who found it necessary to virtually "become European" to find the acceptance they required of themselves. Culturally, Americans had seen themselves as the poor relations of their western European forebears. This has not been the case for many decades now, and Tim Richardson's Great Gardens of America has put that question to rest yet again. The Difference

Most Americans with gardening savvy know this already, so Richardson's survey of American gardens does not even bother making this point. The new thing Richardson brings to the table is an understanding of how American gardens differ from the gardens of Europe. That difference is both a cultural and a historical one. The European garden began with an enclosed space that offered protection from the dangers of wilderness and marauding strangers, the hortus conclusus, essentially a protected courtyard or small walled garden, and it has traditionally kept that sense of inward-lookingness, with a focus on garden structures rather than views into surrounding landscape, and with garden rooms, hedges and walls, borders, ha has that keep wilderness at bay. Even with the 18th century landscape garden, the sense of openness was achieved only by ownership of the entire visible landscape, undertaking vastly expensive manipulations -- moving entire villages, changing the courses of rivers, to achieve the illusion of natural vistas and scenes that were, in fact, highly contrived.As Mr. Richardson points out, American gardens generally are outward looking, with an openness to the wilderness, in many cases even finding their origins in imitation of wilderness. Among wealthy classes with the resources to spend lavishly on their American gardens, and even when designing gardens highly derivative of European gardens, their Beaux Arts or Arts and Crafts gardens took on a character that was newly American, and in the end very different from their European models.

I'll quote directly from Richardson's "Introduction - What is it that makes American gardens 'American'?"

"So what is it that makes American gardens 'American'? The key difference between America's gardens and those of Europe can be traced back to this idea of a society's relationship with nature. Put simply, the American mode of gardening appears to be framed by the nation's historic embrace of the wilderness ideal. Using a necessarily broad-brush approach, it can be observed that American garden-makers have taken a much more open and embracing attitude to the concept and reality of wilderness. This is a theme that struck me time and again in American gardens, which are quite often clearly beholden to European design styles - styles which can then be seen to be have been decisively tweaked or tonally altered. In America, even in cases where the detail of the design was initially inspired by European examples, it seems that the beckoning natural landscape will often be harnessed to set the tone of the garden as a whole. Vistas in America, for example, can just as often be wide and general, as opposed to object- or building-focused, as they are in Europe. This lends many of these gardens an expansive, unbounded feel, quite at odds with the European tradition where an attempt is often made to fence out wilderness by means of enclosures. Even the English landscape park, an ostensibly 'naturalistic' approach to garden making, had as its object a highly particular version of the pastoral which often involved redevelopment of the existing topography. The view may have been expansive, but it was always clearly under control: managed. The European mindset of enclosure was given its richest artistic expression in the cellular Arts and Crafts gardens of the early twentieth century. There are several examples in this book of the ways in which the enclosure instinct was usurped or altered by American garden makers.

These differing attitudes emerged from specific historical contexts. In Britain, for example, from the medieval period, another word for wilderness or unfenced land was 'waste'; it was considered the domain of bandits and dangerous wild animals. In America such places early on became synonymous instead with the idea of plentitude and potential, at least in the mind of the populace at large, as opposed to those who actually lived out their lives on the frontier."

The Critic

Richardson calls it as he sees it. While he finds a great deal to admire at Stan Hywett, a renowned Arts and Crafts garden in Akron, Ohio, he is very critical of the garden's management, which has let parts of the original garden fall into disrepair while using scarce funds unwisely to introduce an "unattractive new conservatory with gift shop and 'butterfly world', various poorly finished paths and roadways ... and a massive Great Garden, which was clearly over-ambitious in that the levels of maintenance needed to keep such a large area of intensive horticulture ... in pristine condition are, it would appear, simply not available at the property. It seems an odd decision, too, for the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company to sponsor a new garden in front of the conservatory while those areas of Stan Hywett's landscape that were developed by the firm's founder suffer serious maintenance problems. One cannot blame the gardeners; this is a management issue. It is to be hoped that Stan Hywett's trustees - and a new chief executive who should be in post by the time this book is published - will in due course redirect such resources that they have away from ambitious new projects and towards core elements of the historic garden..."This is an exciting book. It is a joy on a purely visual level, and it offers much more to those who want to learn something new about some of America's great gardens, who want to better understand why they are great, how they relate to their historic precedents in other parts of the world, and why they are unique to this continent and the places in which they exist.

James Golden