Heartbreak Landscape: Arts and Crafts in Doylestown

Little known, except among followers of the Arts and Crafts movement, is a rather extraordinary group of buildings in a pastoral setting on the outskirts of Doylestown, Pennsylvania. Fonthill, a hand-built concrete castle -- even the roof is concrete -- the home of Henry Chapman Mercer, and the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works, located nearby in the same park-like setting, are both on the National Register of Historic Places, and both are outstanding -- though I think rather atypical -- examples of the Arts and Crafts style.

The landscape in which these buildings sit is astonishing, a dramatic contrast with the small-scale, residential character of much of the surrounding area. And it is the landscape that is really the subject of this post. For this reason, a third notable Mercer building, the Mercer Museum, located in another part of town, isn't of concern here. Henry Chapman Mercer built all three buildings himself, with the help of a group of workmen and a few horses or mules for motive power.

|

| Fonthill, Henry Chapman Mercer's Home |

Mercer, a wealthy single man who found his idiosyncratic place in a corner of the Arts and Crafts world, conceived his home, hired help to build it, and apparently started construction with no formal plans. He even developed the construction methods by trial and error, shaping interior spaces with earth and wooden supports, and pouring concrete into the voids to form the structural elements. All the interior spaces, the walls, floors, stair cases, even the interior bookcases are of a piece, a single molded, three-dimensional mass of reinforced concrete -- almost like a living organism, or the shell of a once-living organism. It's not a warm, cozy place, and it raises disquieting thoughts about why Mercer built it, why its inner structural flow of convoluted rooms, twists and turns, dark passages, is in such contrast to the rolling lawns and open landscape surrounding it. Who was Henry Chapman Mercer and what motivated him to build this singular building?

This little we do know. As a boy he traveled frequently in Europe with his mother. He attended Harvard and graduated without particular distinction. As a young man, he spent about a decade traveling throughout Europe, largely in houseboats. At some point, he is thought to have acquired gonorrhea, which at the time wasn't curable, and is sometimes given as the reason he never married. He worked for a while as an archaeologist, and was especially interested in the native American cultures of his part of Pennsylvania. He developed an interest in ceramics, particularly use of traditional methods for creation of artisanal tilework, that eventually resulted in the creation of the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works. He burned all his personal correspondence and papers before his death in 1930, leaving a blank slate in place of a personal history.

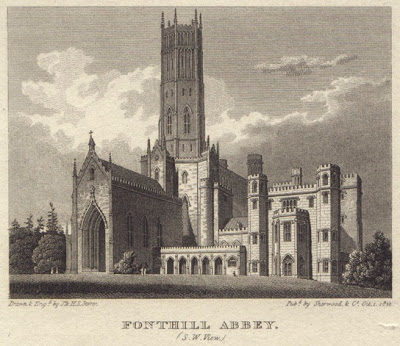

Though I can find little in the way of actual documentation, it appears that Henry Mercer must have been influenced by the much earlier Fonthill Abby, another idiosyncratic structure built by the enormously wealthy William Beckford in England at the turn of the nineteenth century. The earlier Fonthill was probably one of the first Gothic Revival buildings in England, hearkening back to an earlier, idealized period, in much the same vein as the Arts and Crafts movement in America a century later. The English Fonthill was also built of unusual materials -- rough stone bound with mortar and covered with a sand coating to resemble stone -- but in this case simply for speed of construction rather than artistic principle, or to experiment with use of new materials for artistic pursuit. The earlier Fonthill's central tower was almost 300 feet high, and it collapsed several times, eventually leading to destruction of the building. Interestingly, Beckford has a reputation for having large numbers of young men in residence with him at Fonthill, and earlier in his life was accused of having an intimate relationship with the teenage son of a friend, an event that led to his withdrawal from England to France for a number of years.

The Pennsylvania Fonthill sits photogenically amid acres of rolling lawn edged by woodland on two sides and modern roads on the other two sides, though I imagine it was much more isolated when it was built from 1908 to 1912. An elevated entry drive lined by Sycamores gives a formal approach for the few who use it, and the branches of the trees effectively block views of the entire house, allowing only tantalizing glimpses as you approach, enhancing the dramatic effect of seeing this idiosyncratic building close up.

Representing a single individual's artistic vision, though perhaps a retrograde one, Fonthill is a far cry from the more domestic style of such practitioners of the movement in America as Gustav Stickley, the Roycroft Studios, Greene and Greene, the domestic Arts and Crafts bungalows sold by Sears and Roebuck, and even early Frank Lloyd Wright. Quite a wonderful collection of artists and visionaries we label with the Arts and Crafts rubric, isn't it -- a collection of apples, oranges, peacocks, and misfits, so to speak, all working to reawaken the spirit of individual artisanship in an increasingly industrial age of mass produced goods.

And then there's the British side to it all, where it started really, with John Ruskin as philosopher in chief. If Beckford's Fonthill Abby is Gothic (or Gothik) Revival, I'd have to say Mercer's Fonthill looks more "Hobbit Gothic," though that's an anachronistic reference, I know. A joke, really.

As to the Fonthill landscape, the buildings are set amid a great lawn with, as noted, an entrance allee of Sycamores, a surrounding woodland of largely native trees, and a few magnificent specimens near the house, such as the immense Sweet gum (Liquidambar styraciflua) shown below in its autumn garb.

|

| An ancient Sweetgum |

I can imagine some of these details on a Mercer tile, since many of them do reproduce naturalistic detail in just this vein.

|

| Entrance Allee of Sycamores |

|

| Surrounding Woodland |

The Moravian Pottery and Tile Works

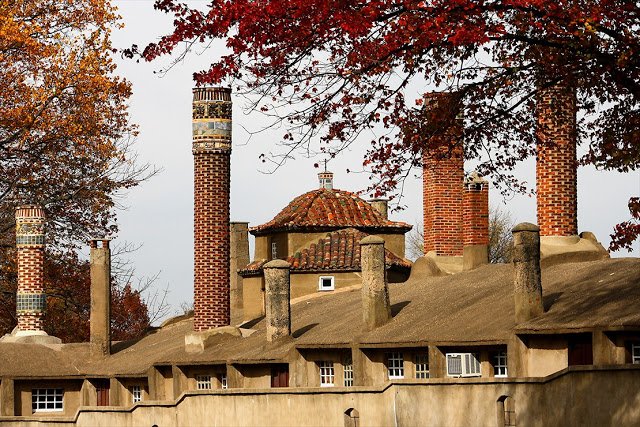

Also an essential component of this landscape is the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works, built by Mercer only a few hundred feet away on the same estate. The tile works grew out of Mercer's desire to revive the Bucks County tradition of pottery making. When that failed, he turned his attention to hand-crafted tiles and thereby became one of the lights of the Arts and Crafts movement in this country. Mercer built the tile works in the Spanish mission style (see below), using the same poured concrete technique used at Fonthill, almost contemporaneously with construction of the house.

|

| Moravian Pottery and Tile Works |

The chimneys, many decorated with tiles made inside the building, and their varied materials and heights, are a striking, almost garden-like, adornment, and contribute much to the visual appeal of the tile works, as well as the landscape.

Carefully placed tile work is used sparingly to ornament the facades, and the concrete roofs are, ironically, quite reminiscent of thatched roofing from a distance. Note even the window mullions (below) are covered in concrete.

The material (concrete) and the technique (simple pouring) at first seems modern, until you remember the Romans invented concrete, and used it extensively in such buildings as the Pantheon in Rome (huge masses of mostly out-of-view concrete stabilize and anchor the massive dome). The rough, textured surface and mottled coloring (below) create a look of antiquity in a building barely a hundred years old.

The Moravian tiles quickly became widely admired and have been used in buildings around the world. The tile works continues to be active to the present, and sponsors apprenticeships, through the Bucks County Department of Parks and Recreation, that have helped keep alive an active tile-making and ceramics community in the area up to the present day.

The Landscape: A Word on Mood

These buildings are not happy places full of light. They all carry a heavy, melancholy air, almost a sense of longing, or perhaps more accurately, of loss. This is especially true of Fonthill. The dark interiors, relatively small windows that give little light, and an ascetic quality are in marked contrast to the brightly lit, open, flowing, visible landscape. Even though Fonthill does have some large-scale fenestration, it is mostly dark and close, full of changing levels, awkward turns, and convoluted passageways.

I'm interested in this because I view Fonthill, the tile works, and the setting as a landscape, as a single entity greater than its constituent parts. I well remember my first view of it while driving by, probably almost a decade ago. It was arresting, exciting, pulled me to it, though I had somewhere to go and drove quickly on. But it certainly got my attention, and lingered in my mind's eye like a haunting vision. And I came back. From any direction, the broad lawns, and the striking silhouettes of the buildings, draw your eye across the wide expanse of space, creating a powerful sense of anticipation. You can feel the buildings pulling you inward.

But once you enter, you're confronted with questions, then mystery. Certainly this is intentional. I'm tempted to try to interpret this landscape using Freudian concepts: tall, vertical, bejeweled stacks representing repressed phallic desires, dark interiors that hide those desires ( perhaps from Mercer himself), sublimation of unknown, or denied, desires into artistic endeavor. I know this is dime store psychology, but it feels so right I can't avoid stating it.

Though I've often seen tents for weddings and celebrations on the grounds of Fonthill, I can't characterize this landscape as one of gaiety and cheerfulness. To my mind, a somber quality permeates the place. This is a landscape of sadness, a heartbreak landscape, full of melancholy and longing, expressing not a sense of fulfillment, but one of withdrawal and loss. A sad and beautiful place.

James Golden