Amalia Robredo: New Directions in South America

| Delicate and graceful Eryngium elegans, one of the many Eryngiums native to La Pasionaria, Amalia Robredo's naturalistic landscape garden on the coast of Uruguay. |

Recently reading Tovah Martin’s article on New York’s High Line in Horticulture magazine, I did a double take when I read this: “Some may argue that it’s too wild and free to be a real garden...” I don’t know why I continue to be surprised when reminded how ubiquitous is this conventional view of gardens. I don't think Tovah Martin intended to say the High Line is not a garden—in fact, I'm sure she meant the opposite—but she did give voice to an opinion among the general public that is much too common—and wrong to my mind.

| View across a prairie of Cortaderia selloana to the monte and house crowning the hill. |

Last fall, when a visiting friend commented that my garden wasn’t really a garden, that it was, in fact, too wild and naturalistic to be a garden, I was surprised enough to write a post on often overly conventional, and complacent, expectations of gardens. I felt a bond with a kindred spirit when Amalia Robredo, a landscape and garden designer (paisajista) in Uruguay, told me about her reaction to the post. “I couldn’t stop laughing,” she wrote, “as I felt so much the same! It happens to me ALL the time.”

So this conventional view of gardens appears to be multicultural, to say the least!

| Built of local stone, the house rises from the monte of native trees, shrubs and other successional vegetation, suggesting stone fortresses that lined the coast in early colonial times. |

Amalia Robredo’s Garden: La Pasionaria

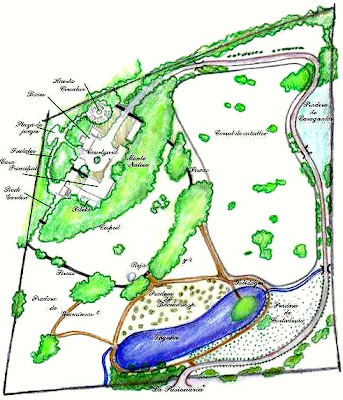

All of this is preface to the story of my recent visit to Amalia Robredo’s landscape garden, La Pasionaria, in Uruguay, a large, 5 hectare—more than 12 acre—garden of prairies, meadows, and native dwarf shrub and small-tree woodland called the "Monte." The monte is a signature feature of the landscape in this part of Uruguay and, though now protected by law, it continues to be endangered by farming, commercial development, and simple ignorance of its important ecological functions.

As Amalia explains it, the monte is an association of trees and shrubs that has evolved over hundreds of years. In the sandy soil of the Uruguayan coast, grasses first take root, protecting the soil from erosion and gradually building up organic matter. As the soil becomes more fertile, new pioneer plants take root, these are replaced in turn by new generations of plants as soil conditions improve, gradually leading to formation of the monte, the climax stage of vegetation in this coastal area.

Amalia's garden sets the standard for preservation of the monte, and it demonstrates a highly successful, relatively easily maintained, and beautiful solution to preserving this aspect of the area's culture and ecological heritage.

This is highly naturalistic garden, unlike the more traditional gardens ("yards") most North Americans expect, and I know from personal experience that some if not many U.S. gardeners may well question whether this garden—or the High Line, or my own garden, for that matter—is a “real” garden. I raise this point here simply because Amalia says she hears the same comment "all the time." In both cases, in North America and in South America, the comment is heard from those who come from cultures that value other kinds of gardens (small gardens, formal gardens, gardens with lawns and flower borders, gardens with fountains and elaborate ornamentation, you make your own list...), or from those who are simply not aware of the variety the word "garden" can encompass.

In early February, I traveled with my partner Phil and several friends to Argentina and Uruguay. I had read about Amalia and her work in Uruguay on Noel Kingsbury’s blog over two years ago when traveling with friends to Argentina on a previous visit. At that time, I hadn’t been able to find any information on gardens there, so I sent an email to Amalia—a shot in the dark, just to see if she would help me. I was amazed to get not just an answer, but to receive a generous offer to help in any way. So Amalia acted as a kind of “cyber tour guide,” answering my questions, and suggesting areas I might want to visit.

| The entrance is designed as a traditional, culturally appropriate structure that might be found on a rural estancia. There is whole-hearted welcome, but no room for grandeur or ostentation here. |

An Invitation to Visit Uruguay

Last summer, Amalia and I had been in touch for over two years when I mentioned to her that the same group of friends and I were planning a return trip to Argentina. She encouraged us to visit her part of Uruguay (close to Buenos Aires), near the small, and now very trendy village of Jose Ignacio. She remained undaunted when I told her we would be seven. She promised a time not to be forgotten, and she certainly delivered in spades, with long visit to her house and garden, a walking tour, introductions to her children and her husband, and an al fresco lunch in the garden for eight, in the shade of the monte surrounding her house.

| Lunch in the shade and coolness of the monte. |

Amalia named her garden La Pasionaria, for the Passion flower, a plant native to the area, and passion is an appropriate word for her depth of feeling for this landscape, its history, culture, and its botanical heritage. With her work, Amalia is breaking new ground in South America, where there has been little interest in naturalistic gardening using native plants. Most public gardens, and many private ones, are still heavily influenced by the 19th century Beaux Arts public gardens and traditions inherited from Europe—with, of course, some major exceptions; Roberto Burle Marx in Brazil, for example. There is a nascent movement, but this kind of garden isn't widely appreciated, or understood.

Only a few minutes into a walking tour of the garden, Amalia and I were excitedly speaking in botanical Latin, much to the consternation of my traveling companions. Amalia had sent me information in advance—references, photos, PowerPoint presentations—so I was already familiar with some of the plants native to her area of Uruguay, and was able to recognize many plants—Colletia paradoxa, Eryngium pandanafolium, Eryngium eburneum, Eryngium sanguisorba, even some genera familiar to a visitor from the northern hemisphere such as vernonia and eupatorium. But there were quite a few new “mystery” plants to be seen.

I describe this background because Amalia’s hospitality and generosity were very much a part of our experience of the garden. That passion extends far beyond just her garden. Amalia is working with others throughout the academic and nursery community in Uruguay as well as other South American countries to identify native plants with potential for garden use, to trial promising cultivars, and to help move them into commercial production. In Uruguay there is no tradition of using native plants in gardens, in fact, no established recognition of native plants as having value in a garden. Many haven't even been identified. Noel Kingsbury has been helpful, and has introduced her to others, including Piet Oudolf in the Netherlands and Cassian Schmidt of Hermannshof in Germany, who also have an intense interest in finding new, garden worthy plants, and putting them to use in sustainable, low maintenance gardens. Here, Amalia is breaking new ground. She has even sent seed of grasses to Neil Lucas in England for trialing at Knoll Gardens.

|

| Andropogon lindmanii, a native grass, in bloom. |

Theoretical, Cultural and Aesthetic Concerns

To better understand why this garden is an important one, it might be helpful to look more closely at some of its spatial, horticultural, ecological, cultural and aesthetic attributes. Amalia's is a garden of contrasts, of light and shade, wind and stillness, wide views across to the ocean and intimate spaces near the house, of rounded, dome-like shapes—of the monte and rounded masses of various Baccharis species—contrasting with the verticals of Cereus uruguayensis, the spear-like flower spikes of Cortaderia selloana, and tall Eryngium pandanafolium (some of these plants aren't likely to be familiar to you, but there are photos below).

| The verticals of Cereus uruguayensis contrast with the rounded forms of the monte. |

| Another powerful vertical, Eryngium pandanafolium, the largest of several highly decorative eryngiums native to this part of Uruguay. It can grow to eight or ten feet. |

| Eryngium eburneum, another native eryngium. |

This is a landscape garden. It uses space, openness to the surrounding environment, lack of boundaries, undulating topography, easily differentiated landscape features (areas of trees and shrubs, meadows, water) to suggest a narrative of a idealized farm anchored in a particular place and a particular culture—and to suggest a journey, one that pulls you inward to increasing levels of detail.

| View to the ocean from the edge of the monte. |

| Across the lake. |

... a drive (or walk) that provides constantly changing views of the landscape—intermittently revealing then hiding the lake and its wetland plantings, a prairie of species Cortaderia selloana adjacent to the road, across the lake a Baccharis prairie in the mid distance, behind that a lawn then more prairies and meadows—these are in essence very large garden "rooms"—and in the distance a view of the house, built of local stone, thrusting mysteriously up from the monte. The entrance journey ends as you arrive at the residence opposite the entrance to the property.

| The entrance drive provides changing views of the 12 acre garden of prairie, meadow, and monte. |

| Reclaimed rusted wrought iron embellished by a planting of Paspalum quadrifarium and Paspalum plicatulum. |

I use the word “elegant” in the way a physicist would describe a theory that accounts for many complex phenomena in the simplest way possible as an elegant theory. Amalia’s elegant and refined composition is successful as much for what she left out as for what she put in. It is a restrained and subtle garden. She has used a very light hand, carefully editing preexisting parts of the landscape. Even where major new features have been created—the house and the whole residential complex, a large lake, massive stone walls and gates separating the residential and utility areas from the wider landscape—they look as if they always existed.

The garden entices the visitor by drawing the eye to nearby plant textures and shapes, then carries the view to the forms, shapes, colors and textures of the distant landscape. This is especially evident in the two images at the top of this post—in the close-up view of Eryngium elegans and the landscape view across to the monte and the house.

Near the end of the entrance drive, a tall stone wall and heavy wooden gates announce your arrival at the house and its immediate precincts ...

... where the garden is realized on a smaller scale, incorporating areas for recreation, pleasure, and utility in an ordered counterpoint of stone, water, light, shade, and ornamental ironwork—all carefully planned but with a relaxed. informal feeling.

| The Courtyard |

| Pterocaulon balansae |

| Eryngium elegans |

|

| Eupatorium macrocephalum flowering in the trial border. |

The Courtyard is quite large. Here, in a lighthearted moment that captures something of the spirit of her garden, Amalia is playfully pointing to a grasshopper on a Spartina ciliata ...

The Courtyard also makes room for parking and garages, a stable for horses, a playground for the children, and on the other side of an inner wall, through an ancient door salvaged from a prison in Montevideo, a "summer kitchen," pool and lounging area, and a dining area—all are efficiently and unobtrusively organized within the shelter of the monte.

| An old wagon-mounted carriage at the entrance to the children's play ground. |

| Lounging area beside the pool. |

Even the monte has its own unique vegetation adapted to more protected, fertile and shady conditions. Amalia has made paths through the monte so you can walk in seclusion, observing the different plant communities that live in the shade, such as these ferns ...

| Blechnum australe ssp. auriculatum. |

... in other parts of the monte openings to the wider landscape dramatize the contrast between dark and light, shade and bright sun.

At a maximum height of probably less than 20 feet, the monte has an intimate, human scale. You can stroll on shaded paths throughout the Coronillas (Scutia buxifolia) and Canelones (Rapanea laetevirens), the small trees that predominate in the monte, walking at full height, with ample room to move about. Amalia refers to the "green rooms" within the monte as giardinos segretos (secret gardens).

Other paths reveal the sky while completely hiding the landscape outside the monte.

But a few steps can take you into a different world, the bright sunlit countryside ...

... and a stroll across the lawn, past meadows and prairies. According to Amalia's maintenance regime, a prairie is cut once a year or less, while a meadow is cut more than once a year, the frequency depending on the makeup of the plant community. Well timed cutting is necessary to allow desired grasses and flowering perennials to mature and seed, while preventing less desirable plants from getting out of hand.

The lack of boundaries gives the garden a tremendous feeling of openness and endless space, here enhanced by the downward slope of the terrain as it drops away toward the beach and the sea. The low, dry laid stone wall, called a pirca locally, divides the lawn from the meadows and prairies beyond.

Although it was extremely dry following the summer drought, the prairie still revealed a rich community of plants. Here you see the seed heads of Eryngium sanguisorba amid grasses ...

When I jumped over the pirca to take a closer look, Amalia quickly called me back. It seems snakes frequent the high grasses, so it's safer to keep to the closely cropped lawn when taking a sunlight stroll.

A walk down the gentle slope brings you to the lake and a pathway across the dam ...

Here, a view from the other side of the lake, magically capturing a piece of the blue sky.

Unlike gardens that start with a blank landscape (if there be such a thing; I doubt it), La Pasionaria does not impose a design on the land. The existing landscape, and in particular the monte, takes center stage.

Amalia's approach is one of enhancement and preservation and it is, I think, probably the garden of the future. In a world of increasingly scarce resources, lack of access to labor, financial constraints, water shortages, and environmental degradation, this kind of sustainable garden offers an attractive and viable solution to both resource constraints and preservation of the environment, genetic diversity, botanical heritage, and culture—one that can serve as a model for larger and more encompassing preservation efforts that will be needed—a way of maintaining beauty in an increasingly tarnished world.

(Selected photos courtesy of Amalia Robredo and Phillip Saperia. Drawing courtesy of Amalia Robredo.)

James Golden